A friend asked, “How can something that is selfless be reincarnated?” Firstly, let’s change question from one about “reincarnation” to “rebirth.” This will make things easier. Reincarnation is a broad term that has expressions in many traditions. In the Indian context, it was an assumption that everyone shared and still shares in a significant way. In the Greek context it is known as metempsychosis, and survived even into Christian times, but was eventually made a heresy and mostly disappeared except in pagan or other liminal contexts. Nowadays there are various New Age versions of a reincarnation doctrine, but mostly it is just a vague and unarticulated cultural belief for those that have it.

In Buddhism, there are various versions but I’m not familiar enough with them to answer the question in an academic way. But since you are asking, I think it is important to understand reincarnation in the context of the Dharma as “rebirth.”

The emphasis on rebirth shifted or dissipated when Buddhism went into other cultures, but it is still fundamental, and contrary to what some secular Buddhists claim, eventually unavoidable.

“How can something that is selfless be reborn?”

With this question and many others, it is important to recognize that this is an instance of a whole class of questions whose nature is essentially the same. They are all the same question, put in different ways and assume different starting points. It can be really confusing when it seems like there are so many paradoxes in the dharma. It is really liberating to be able to recognize how various paradoxes are all renditions of one essential paradox. We could say the essential paradox is between emptiness and compassion, or emptiness and form. Sometimes the essential paradox is understanding how the inside and the outside, subject and object, both create and negate one another. It goes on and on.

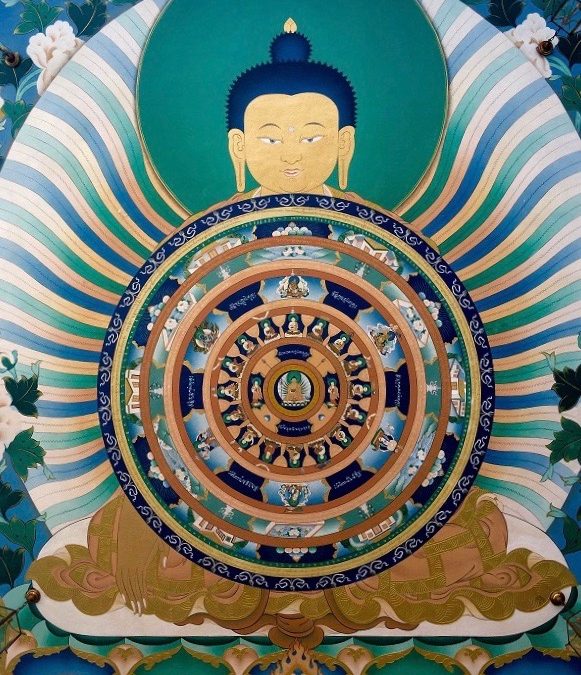

When using reason, the mainstream philosophical schools of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism approach this issue through an understanding of the two truths. Relative, provisional, or “totally fictional” truth relates to everything that has a name, and how it all functions. Ultimate, or definitive truth is shūnyatā, or emptiness. The integration of relative and ultimate is the ground and goal of all Mahāyāna (and Vajrayāna) Buddhist paths.

When using the path of reason within Mahāyāna Buddhism, the question of how the relative and the ultimate relate is traced through an increasingly subtle progression and maturation of conceptual understanding, developed in tandem with meditation and direct experience.

At first one learns that the solidity of outer appearances is actually a field of atomic particles, all of which are constantly changing and mostly composed of empty space. Relatively things appear as solid, ultimately things are a field of particles. One then meditates on one’s body and the environment as a dynamic and spacious flux. The singular idea of “my mind” is also taken apart into its constituent parts and understood to be a process. Relatively we can say “my mind”, but ultimately it is a process of parts. These reflections loosen one’s identification with “self” and one’s fixation on “reality.”

Then gradually one learns to see things as being like a dream or holographic display. Relatively things appear real, while ultimately they are dreamlike and insubstantial.

At a certain point one explores a very subtle view of relative truth that sees mind and matter as creating one another in a dance that erases itself as it evolves, like writing on water. The self is a creative fiction, dancing in space. Ultimately, mind and matter are empty of any concept we might have about them.

At this point, the relative and ultimate become so indistinguishable that the relative way things appear is in harmony with how they actually are: totally clear and yet totally insubstantial. At that point, the relative and the ultimate pour into one another, like water into water.

When we ask, “how can something that is selfless be reborn?”, we are asking a question about relative and ultimate truth. This means that the answer is related to what we believe to be real, and how we experience the nature of our mind.

Relatively, we have the idea of ourselves as a self, and we think when we die, we become nothing. Or, we believe in the idea that when we die, we are reborn, either in a heaven, a hell, or again on earth, or maybe even in the Pleiades. Or we believe in the idea that when we die, we become “one with everything.” Or maybe we are comforted by the poetic idea that our molecules get spread around the earth enough to the point that we become a part of the clouds, the rain, and in the bodies of every person and being on the planet. We are all stardust, after all, just like whatever became of Carl Sagan.

But to adequately answer the question it is important to go beyond ideas, to go beyond the thinking mind. We can trade gross ideas for subtle ideas, and subtle ideas for more subtle ideas. But if we fail at some point to go beyond thinkable things, we will miss the point of the Dharma. The practice of the Dharma is to trade gross ideas for subtle ideas, in order to go beyond ideas altogether.

Ultimately, there is no rebirth. At the end of the day, every Buddhist accepts that. Therefore, there is no need to defend the doctrine of rebirth from anyone that wishes to water it down and whitewash it. But it also means that on the relative side, we need to pay close attention to the precise way in which we will not be reborn, otherwise things become repetitive and nauseating. This is known as the cycle of rebirth, or saṃsāra.

In “how can something that is selfless be reborn?”, there are two things, “self/selfless” and “rebirth/no rebirth.” In both cases there is a relationship between something/nothing.

It makes sense that something can be reborn. It also makes some kind of sense that if we are a selfless nothing, nothing happens when we die. It also makes some kind of dreadful sense that our self can become annihilated at the time of death, and something becomes nothing. But it is hard to make any sense of something selfless being reborn.

In actuality, the first three scenarios are all refuted by Buddhist logic, and only the last is seen to be possible. I won’t go into those arguments, but they all amount to biased ways of viewing the relative and ultimate truths. They are either nihilistic or naïvely realistic.

When the substantial version of the relative truth is privileged, we end up saying that we really have a true self, and it truly is reborn. When a nihilistic version of the ultimate truth is privileged, we either say we are something that becomes nothing (like scientific materialism) or we are nothing and are released into nothingness at death (like nihilistic existentialisms).

When the middle way between something/nothing is discovered, relative and ultimate truths are a natural integration. Without being biased toward either being or not being, we understand ourselves to be insubstantial, relative selves with no core or ground, deeply interrelated with all other things, inside and out. The continuity of that relationality never stops flowing until Buddhahood, and can never be found or named or contained. (In the Vajrayāna, the continuity is found and named and contained in the context of yogic experience, but that is another story.)

This integration of the two truths is called “insight into the unborn.” Unborn means beyond the duality of birth and death. When we look clearly at our mind, it is seen to be unborn. Since it has no parts, it can’t fall apart. It was not born or made, and therefore it cannot die.

We can have this insight that our own mind is unborn, and we can see that all phenomena are unborn too. We see that thoughts arise in the emptiness of mind and go back into mind, we see that all appearances similarly arise from, abide within, and recede into mind. And when we look at mind, it is empty. Yet it expresses itself constantly, incessantly, spontaneously. And yet it erases itself in the moment of its expression, uncatchable, ungraspable, like a song in a dream. The rational approach we have used until this point is then complemented with meditative experience. We can become familiar with this through the practice of insight meditation, or vipashyanā.

So, something that is unborn cannot die. And something that is unborn cannot be reborn, either. It is a continuity unstained by any concepts of birth or death, concepts of something or nothing. Though this continuity isn’t subject to rebirth, it naturally emanates in whatever way is beneficial to beings trapped in the cycle of birth and death.

When we are not in touch with our true nature, we are unable to remain in the immaculate conception of the unborn, and so we are constantly giving birth. We are giving birth to concepts, emotions, and actions that become reactions, emotions, and ever more concepts, all eventually becoming a tremendous burden. We carry this baggage from day to day, year to year, and from life to life. Even materialist studies of epigenetics demonstrate something similar.

The point is to suspend this cycle of conception and birth that are the causes of rebirth. When we are able to develop familiarity with the unborn nature of self and reality, we are able to stop the cycle of birth and the cycle of suffering. At that point, this freedom inspires us to re-inhabit the relative world as a bodhisattva, deliberately taking birth in whatever way is most beneficial to sentient beings. Since this process of “birth” is arising from wisdom, it is unrestricted in the way it can appear, and does not create the causes for being or non-being, only freedom.

As is said in Shantideva’s Bodhicaryāvatāra:

May I be protector for those without one,

A guide for all travelers on the way;

May I be a bridge, a boat and a ship

For all who wish to cross (the water).

May I be an island for those who seek one

And a lamp for those desiring light,

May I be a bed for all who wish to rest

And a slave for all who want a slave.

May I be a wishing jewel, a magic vase,

Powerful mantras and great medicine,

May I become a wish‐fulfilling tree

And a cow of plenty for the world.

Just like space

And the great elements such as earth,

May I always support the life

Of all the boundless creatures.

And until they pass away from pain

May I also be the source of life

For all the realms of varied beings

That reach unto the ends of space.

Through confusion, self-centered sentient beings are born again and again, “dying many times before their deaths,” becoming ever more burdened, blown and thrown by the strength of their habits into new rebirths. Through penetrating insight into the unborn, bodhisattvas intentionally take illusion-like births, time and again to benefit beings.